GBR | Geology of Britannic Repair

For the 19th International Exhibition of the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2025, the British Pavilion—commissioned by the British Council—was curated by Cave_bureau in collaboration with Kathryn Yusoff and Owen Hopkins. This marked the first time in its history that practitioners from Britain and Kenya jointly curated the pavilion.

Curatorial Brief

Architecture is an earth practice. Every building is an intervention in the earth’s geology and inevitably a mine, with Its materials deriving ultimately from the ground. As a consequence architecture has long acted as both a manifestation and driver of ongoing processes of geological extraction, which have led to the present climate emergency unfolding globally. These extractive processes are bound up with the history and present realities of colonialism of which the Anthropocene – the geological age of humans – is the outcome. The architecture that’s come to define this era has broken the deep connections that have long existed between people, ecology and land. This exhibition explores a new relation between architecture geology and people.

Disrupted neoclassical facade of the British Pavilion, titled ‘Double Vision’ using a veil of carbon and clay taking the shape of a Kenyan Maasai Manyatta home.

Curatorial Theme

Re-centring architecture’s relationship to geology as crucial to how we understand its past and present, but also to how we might re-orient its future otherwise. GBR: Geology of Britannic Repair is a unique UK-Kenya collaboration that sought to unearth such “other architectures” that offer possibilities for repair, restitution and renewal.

The exhibition’s geographical, geological and conceptual focus stems from the British Pavilion’s pivotal alignment along an axis that runs between Britain to the north-west, and Kenya and the Great Rift Valley to the south-east. Emerging from this “rift” are a series of installations that propose architectures defined by their relationship to the ground, their resistance to conventional, extractive ways of working, and that are resilient in the face of climate breakdown and social and political upheaval.

Rather than offering solutions, the exhibition aims to unlock what architecture and colonialism have long marginalised, activating the British Pavilion as a site for reimagining the relationship between architecture and the earth.

Photographs of Double Vision ‘Veil of Carbon & Clay” by Dudley Waltzer

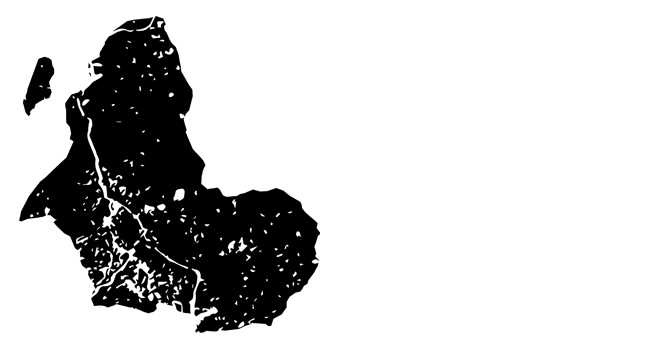

Double Vision: “A veil of carbon and clay.”

What do you see when you look at this building? The neo-classical façade or the veil that enshrouds it?

The veil’s shape is inspired by the form of the Kenyan Maasai people’s traditional manyatta dwellings. Built from locally sourced branches applied with mud, cow dung, urine and ash, manyattas are characterised by their single entrance and curved profile. They can be quickly built and rebuilt to suit a nomadic way of life.

The agricultural waste briquettes, clay, and glass beads from which the veil is formed have multiple origins and resonances. The briquette and clay beads have emerged from the Kenyan earth and been fashioned by Kenyan hands, echoing the traditional practices of Maasai women, who are the original master builders of their homesteads. The glass beads are from India, and in this context recall the ornamental beads made in Murano which were used historically as a crude imperial currency for exchange of metals, minerals and enslaved persons.

Casting the British Pavilion in a black, brown and red hue, the veil makes visible the “other earths” that empire displaced, inverting the project of colonial conquest that forced colonised peoples to see oneself through another’s eyes. The veil obscures but it also reveals.